| |

An

18th-century source of the 'Batali'

The

'Batali' [NVE 47] is a strange piece in Jacob van Eyck's Der Fluyten

Lust-hof. Neither a variation work nor a free fantasia or prelude,

it is a work depicting and imitating a battle. As Ruth van Baak Griffioen

suggests, van Eyck might have played his 'Batali' with the bells of

Utrecht whilst celebrating Dutch military victories. [1]

The carillonneur is known to have participated in such celebrations

at several times.

Battle pieces are usually full of clichés,

such as triadic trumpet calls, drone basses and drumbeats. Van Baak

Griffioen has analysed the 'Batali' and found a lot of similarities

between its motives and those in other selected battle pieces, by

Jannequin (his most famous chanson), Vallet (lute), Byrd (keyboard)

and other composers. The genre must have been quite popular.

|

|

| |

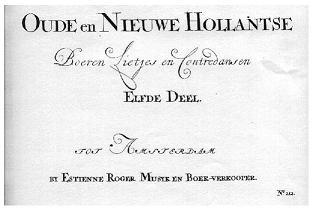

Under No.

789, the eleventh volume (c1715) contains a piece called 'De slag van

Pavie' ('The battle of Pavie [Pavia]'), which shares so many features

with van Eyck's 'Batali' that it seems to have been derived from it.

[Facsimile]

The concordance between the two pieces - which has eluded van Baak's

notice - raises several questions. The burning issue is: does the example

from Roger's collection rely on Der Fluyten Lust-hof, or are

the two works parallel versions of one and the same battle piece, so

deeply rooted in Dutch society that it had its place in the communal

memory of the nation?

'De slag van Pavie' is a strange heading in the light of the musical

content: the piece includes the 'Wilhelmus', in van Eyck's time a symbol

of the revolt against Philip II of Spain. Today, it is the Dutch national

anthem. The song dates from c1568. The battle of Pavia, however, had

already taken place in 1525, and had nothing to do with any Dutch revolt.

Pavia is a city in northern Italy, and the famous battle there was between

the forces of Emperor Charles V and the troops of the French king Francis

I.

It leads us to believe that 'Slag van Pavie' was a common Dutch designation

for battle pieces. This is confirmed by a diary that the schoolmaster

David Beck from The Hague kept in 1624. On 23 September of that year,

he visited the Grote Kerk, 'hoorende [...] wel een uijre lanck de slag

van Pavijen op den Orgel spelen, alwaer veel volck was' (hearing for

the duration of one hour the battle of Pavia played on the organ, attended

by many people). [3]

How do the 'Batali' and 'De slag van Pavie' relate to each other? All

sections and ingredients of van Eyck's piece are present in the later

version, except for the 'drum section' of high and low C's preceding

the 'Allarm'. The corresponding sections have the same order. The 'Wilhelmus'

tune is in triple time in both cases, and not in duple time as usual.

Are these features a matter of coincidence? It is not very likely. Another

battle piece, for lute, has survived from the 17th-century Dutch Republic.

It is by Nicolas Vallet (Secret des Muses II, 1616).

[4]

It again shows similarities too but they are less, whereas the overall

plan is utterly different. Apparently there was not one ubiquitous concept

of a battle piece making its round in the Netherlands at that time.

An organist could even sustain it for one hour, as David Beck informs

us. This gives good reason to assume that 'De slag van Pavie' does rely

on the van Eyck.

But what about the great many differences? Sometimes they are marginal,

other times considerable.

One could call 'De slag van Pavie' a corrupted and - at some places

- simplified version of the 'Batali'. It is interesting, for instance,

to see how measure 12 of the first section has been flattened out. In

Der Fluyten Lust-hof this measure is part of a sequence, and it

is the only place in the whole Lust-hof where van Eyck prescribed

the note D'''. In the 'Pavie' version this was smoothed out completely,

with only two notes C''' remaining, certainly less demanding. [example]

The last

section of 'De slag van Pavie' hardly shows any concordance with the

'Batali'. It is in triple instead of duple time, the alternation between

G' and C" in the first measures is organised differently, and little

remained of the stirring character of the original.

It is clear that the compiler of Roger's collection didn't copy the

piece straight from van Eyck's Lust-hof. The 18th-century version

seems to be the work of a musician - probably a recorder player, unable

to perform the D''' - who remembered the piece only vaguely. It is close

enough to make it identifiable as proceeding from van Eyck, but not

close enough to hold its own against the original. Perhaps the most

important lesson is that van Eyck's mental legacy was still alive even

sixty years after his death...

|

|

| |

Notes

[1]

Ruth van Baak Griffioen, Jacob van Eyck's Der Fluyten Lust-hof (1644-c1655),

Utrecht 1991:

109-113. [back]

[2]

Facsimile ed. M. Veldhuyzen, Hilversum 1972.

[back]

[3]

David Beck, Spiegel van mijn leven, Haags Dagboek

1624, Hilversum 1993: 174. [back]

[4]

Facsimile: Utrecht, 1986. Modern edition: Paris,

1970. [back]

|

|